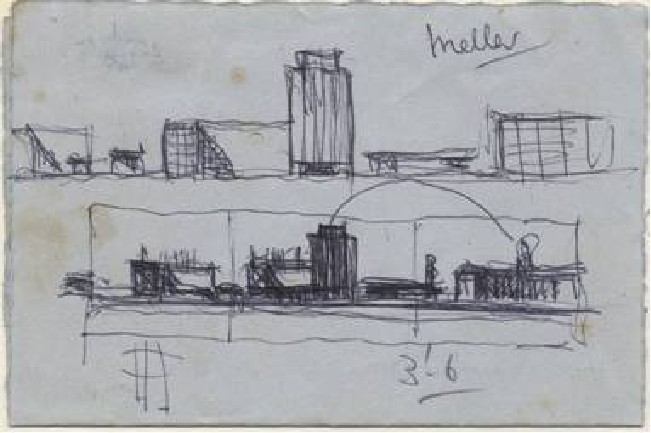

A perspective drawing from the early 1930s.

THE RALPH MAYNARD SMITH TRUST___ ( Registered Charity Number : 1049843 ) |

| Home | Gallery | Biography | Archive of Drawings and Paintings | RMS Trust and Database |

| Exhibition & Projects | Ancillary Archive - Writings | Ancillary Archive - Architecture | Work in Progress |

Click images to enlarge |

Updated July 2017 |

|

|

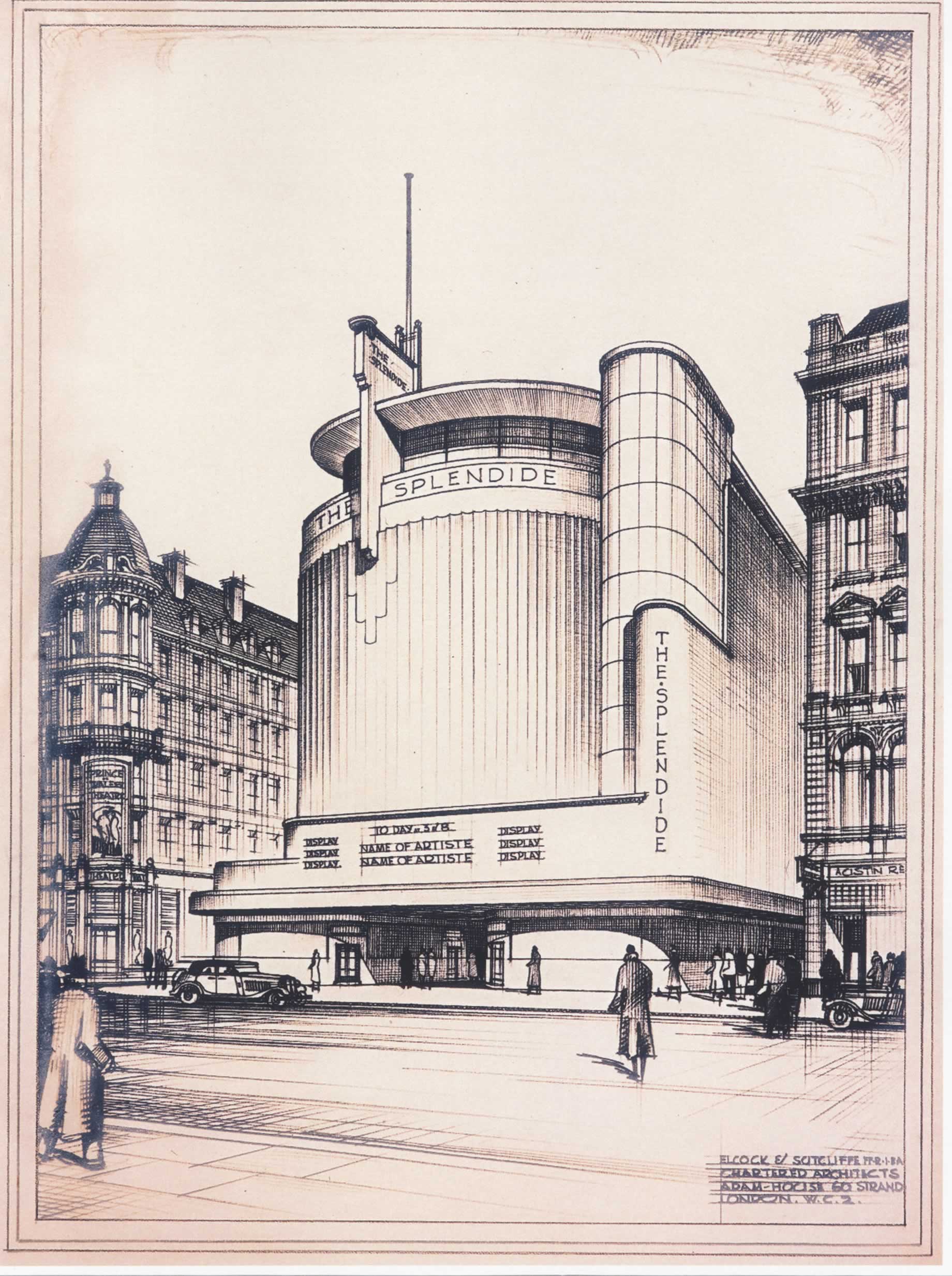

|

| 1. Proposed Oxford Street Store (Elcock & Sutcliffe). A perspective drawing from the early 1930s. |

2. Skating Rink at Sheffield (Elcock & Sutcliffe). Perspective drawing 1931. |

RMS Ancillary Archive (Architecture) |

An abbreviated chronology of his career as an architect runs as follows: RMS joined Elcock & Sutcliffe in 1928, later becoming a partner in the firm. Sutcliffe left the partnership in 1942, while RMS continued with Elcock through the War. Elcock died in 1944, leaving RMS as the sole partner running the business. In 1945 he joined Easton & Robertson, becoming a partner the following year (the firm was later known as Easton & Robertson, Cusdin, Preston and Smith). He worked closely with Sir Howard Robertson in the five person partnership. Much later he suffered from lung cancer, from which he never fully recovered. The evidence reveals a never-ending pressure of work from 1928 to 1963, the year in which he retired. He died the following year at the age of 60.

|

|

||

| 3. “Royal Hotel Manchester” RMS perspective drawing. c.1930 |

|

In the 1930s Elcock & Sutcliffe ranked among the leaders in the field of institutional design, especially hospital design. In 1930 they completed Bethlem Royal Hospital at Beckenham, Kent, which is still flourishing today; then Runwell Mental Hospital in Essex which was opened in 1937 (see illustrations 9-15). That was seen as a pioneering development in the approach to mental illness, and the architects were said to have “assumed the mantle of a physician”. From the mid 1940s to the early 1960s, RMS and Sir Howard Robertson ideally complemented each other as a design team, and a plaque in the lobby of their high-profile Shell Centre scheme records RMS’s contribution. Sir Howard Robertson was an RA, president of the RIBA (1952-4) and a member of the Board of Design Consultants for the United Nations Headquarters in New York. |

||

In 1955 the architectural writer and theorist Hope Bagenal, commented that the buildings of the Easton & Robertson partnership:

“come out of an office where younger men and older men work together carrying on that great tradition of friendliness of that good man Stanley Hall. The office is also a school of building research and a school of aesthetics.” Fifty years later, James Malpas wrote: |

||

This collection contains: 1. Drawings of buildings. Most in portfolios, loose and un-mounted. 2. Photographs of drawings. High quality photographic prints, many mounted on board and authenticated by RMS, in Archive type storage boxes. 3. Photographs of buildings, photo prints, transparencies & digital images on PC. 4. Written commentaries and articles on the buildings, press cuttings. Dimensions: for the larger drawings and plans of buildings require artists’ type portfolios (from A0 size down), plus archive type storage boxes (W98mm x D367mm x H235mm). Transparencies would need appropriate storage unless / until transferred to the digital records. It is hoped that the RMS Archive Collection (Architecture) can remain part of a “Unitary Archive”, so that all three aspects of his work, as artist, writer and archtect, can be kept together; but in the event that it has to be partitioned, the prior completion of a three part database is essential, so that at least in that way a view of RMS’s multi-disciplinary thinking can be saved and assessed. The RMS Trust has prepared an A4 x 48 page fully illustrated review of its architectural collection (in a very limited edition). This will be used as a guide for assembling the appropriate sections of the database & catalogue raisonné. It includes references to RMS’s father’s architectural practice in Cape Town, SA, in the early years of the 20th century.. Having completed the text-only Database of Paintings and Drawings, (recording the main part of its three-part RMS Archive), the RMS Trust now plans:- a). To extend the Database to include the ancillary archives of Writings and Architecture. The architectural component is expected to amount to at least 200-300 items. b). To include illustrations throughout. Ideally the Architectural records will remain part of a unitary Archive although separate locations for its placement may have to be considered. See also “The Trust in 2012” on the “RMS Trust and Database” page. |

|

|

4. The Corinthian Club. (Elcock & Sutcliffe) Perspective drawing of an art deco building, early 1930s. |

||

|

||

| 5. Detail of the Corinthian Club perspective drawing, showing a carved panel high up on the front elevation. It represents a feat of draughtsmanship, for while it in no way disturbs the simple plane of the elevation, it delineates the carving well enough for a sculptor to begin work | ||

|

|

|

| 6. “Proposed Store, Oxford Street, London”. Perspective drawing, early 1930s. Third version of the design (the Trust has 4 versions but there were more than that before it was built as D.H.Evans) | ||

|

||

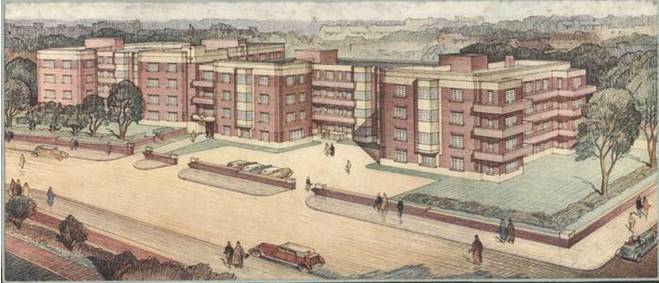

| 7. “Flats” (Elcock & Sutcliffe). Perspective drawing, mid 1930s. Probably the first version of a later scheme for Flats at Blyth Road, Bromley (there is another elaborate perspective drawing of that scheme, dated 1937). | ||

| 8. “Project for a Cinema” (Elcock & Sutcliffe). Perspective drawing c.1935. The drawing dates from about the time that The Odeon, Leicester Square was being proposed. |

|

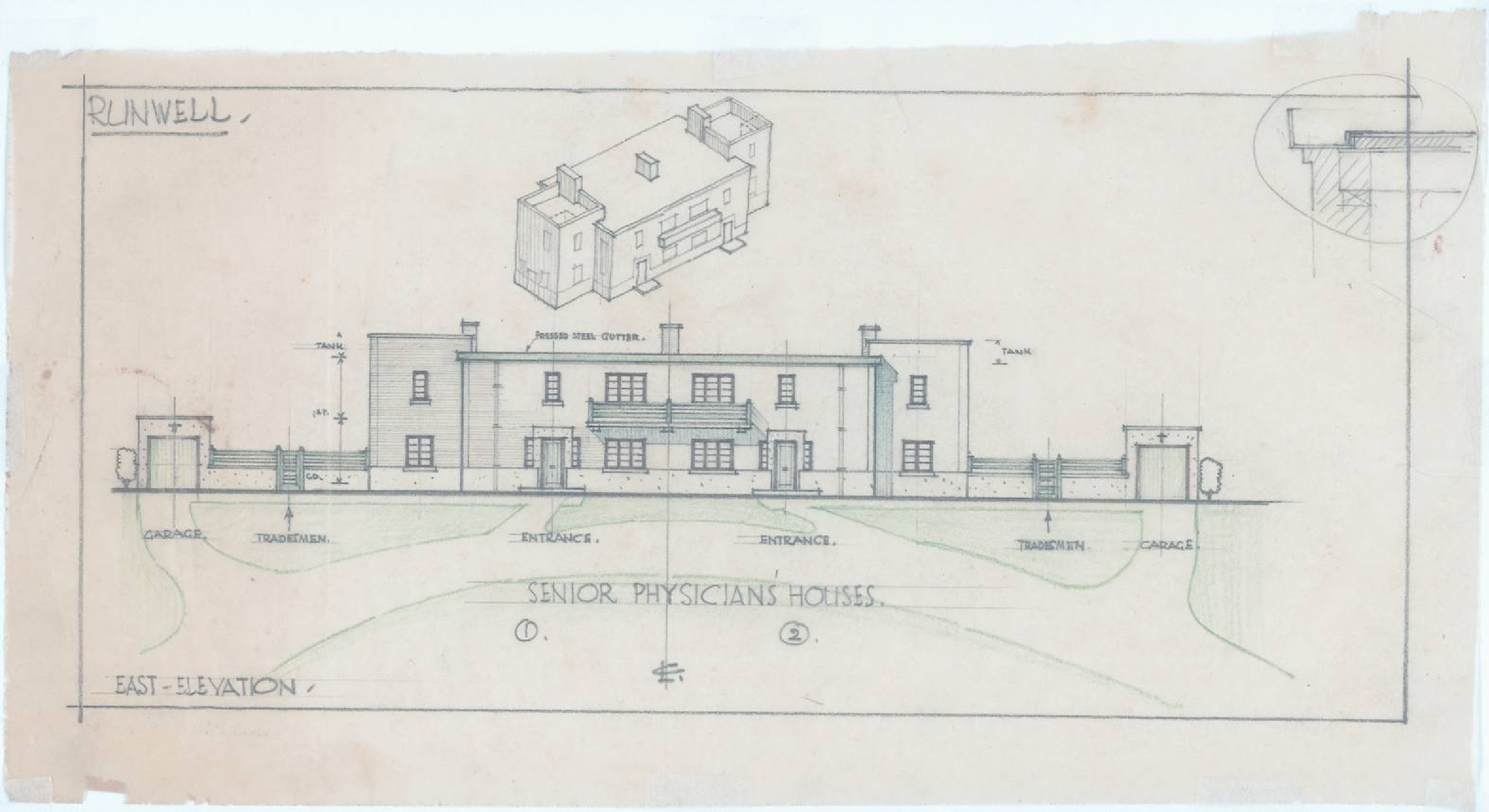

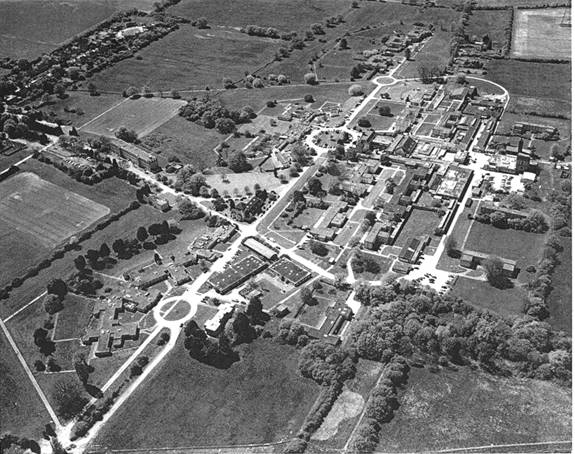

As already mentioned this hospital was seen as a pioneering development in the approach to mental illness, and the architects were said to have “assumed the mantle of a physician”. But it was more than just a hospital, the scheme as a whole was virtually a self-contained village community on a 500 acre site. All the staff had accommodation there, ranging from the Superintendent’s and Senior Physicians’ modernist Houses to the well-appointed Nurses Home and comfortable, gable-roofed Matron’s House, Its 1,000 bed capacity (later catering for nearly twice that number) was organised from the central Administration Building which had a re-assuring feel, with its Georgian fenestration and clock tower. A dedicated Power Station (with echoes of Battersea Power Station? See illustration 13) supplied the whole hospital with electricity. Kitchens catered for the whole hospital, with provisions coming from the hospital’s on-site Market Garden. There was a Chapel placed at a focal point of the site. Educational and Recreational needs were catered for by a theatre with a stage where films could also be shown and talks given. Extensive grounds were designed and laid out as parkland, creating a relaxed environment throughout (see illustrations 9-15). For most of the hospital’s working life these grounds were immaculately maintained, but the hospital finally closed on 9th August 2010, It is thought that both the Chapel and the Administration building may be listed and saved. The site seems likely to be used for a housing development. The aerial photograph, taken around the turn of the millennium shows the extent of this village-like settlement. |

||

|

||

| 9. Runwell. Senior Physicians’ Houses. Drawing c.1929

|

||

| 10. Runwell. The Matron’s House, 2002, shortly before demolition. Photo: B. Claydon | ||

|

|

|

||

| 12. The Administration Building.

|

13. The Power Station. | |||

|

|

|||

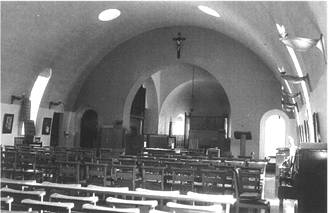

| 14. The Chapel Interior. Photos 2002: D. Banham |

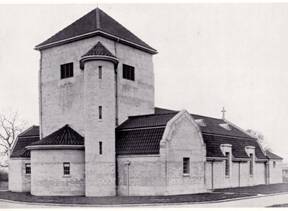

15. The Chapel (in 1937). Runwell Hospital Photo Archive |

|||

11. Runwell Mental Hospital (1928-1937). Elcock & Sutcliffe. Aerial view showing part of the 500 acre site: the playing fields are largely out of the picture to the left, while the original farm and market garden are off the picture to the right: Runwell Hospital Photo Arch.

|

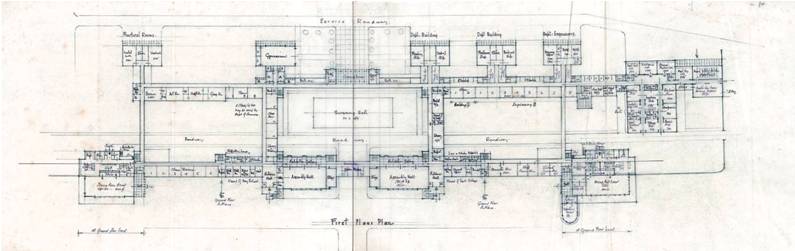

The College and Technical School were opened in 1954 and its buildings have since become the central core of the greatly expanded University of Hertfordshire’s College Lane Campus (see illustrations 17-21). Writing about it ten years after the opening, Ian Nairn said: “A worthwhile, unfashionable building … the building’s personality will never be pigeon-holed. In many ways it is an expert French building translated into English yellow brick and shingles—both of which, incidentally, are wearing well. Two pavilions are sited at either end of an immensely long building, almost symmetrical, which runs under the brow of the hill. The ends are three-storey (college at one end, school at the other), the long links to the centre two-storey, the centre itself single-storey and deeply recessed ... Behind the links both schools develop in big interior courtyards, undogmatic but powerful, and not easily forgotten.” Earlier, in 1952 as it was taking shape, Trystan Edwards referred to its “ … delightful quadrangles linked by an innovative sunken roadway, bordered by gently sloping planes.” For a more objective view of the whole scheme see the perspective drawing reproduced here (17). The location of the original drawing is unknown and the only evidence available is from this badly worn newspaper cutting in the RMS Trust’s collection. But, together with the reproduction of Maynard Smith’s early drawing of the scheme (18) a clear view of the layout emerges. |

||

|

||

| 16. Nurses Home Grantham Hospital. Drawing, 1943.

|

||

|

||

| 17. Hatfield Technical College. 1954. Perspective drawing of the final layout, from a press cutting (drawing possibly by Jim Thring). | ||

18. Hatfield Technical College and Secondary Technical School opened in 1954. An early drawing by RMS (mid-late 1940s). It records probably the first version of the project, which now forms the core of the University of Hertfordshire’s College Road Campus.

|

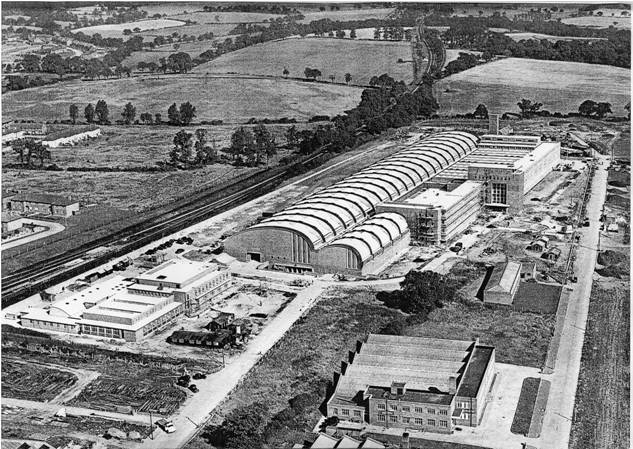

The Bank of England Printing Works at Debden (Loughton), were augmented by the Canteen, Recreation Hall and Theatre Buildings (to the left of the main Works). Later the Returned Notes Building (c.1959) was added (to the left of the site as viewed in the aerial photograph 23) and was itself a distinctive industrial building. The 13.5 acre site also provided extensive playing fields with a two-storey Pavilion, lying out of the picture to the right (see illustrations 23-26)

Gavin Stamp writes: “Amongst the projects with which Maynard Smith was involved was the new Printing Works for the Bank of England at Debden, Essex. Built in 1953-56, this was the firm’s most impressive post-war design, in which the 125feet wide main production hall was spanned by pre-cast and pre-stressed concrete ribs of a remarkable asymmetrical profile which support tiers of north-light shell windows … “ Alongside that scheme with Robertson, Maynard Smith was heading up two other projects: The Printing Works for Bradbury Wilkinson in Pretoria, SA (22), and Alleyne’s Grammar School at Stevenage, where the remit was to create an informal and homely environment rather than an instutional one. The solution is demonstrated by the large Gymnasium and Assembly hall being housed in a gable ended brick building having a ‘domestic’ appearance, as do the other classroom blocks. However, one important façade has been marred by later additions.

|

|

|

| 22. Printing Works Pretoria, SA for Bradbury Wilkinson. Model. c. 1959. Photo: RMS Trust. | ||

|

____ |  |

|

| 23. Bank of England Printing Works, Debden Essex. c.1956, nearing completion. Canteen, Recreation Hall and Theatre on the left | |||

|

|

||

| 24.The Main Entrance. 1957 | 25. Extreme end of the Main Printing Hall | 26. End of the Main Printing Hall and its smaller companion, Photos: Bank of England Photo Archive. The Main Hall provided a working area some 850 feet long and 130 feet wide and the asymmetric curve of its arched roof provided a sense of uplift and airiness from within. |

|

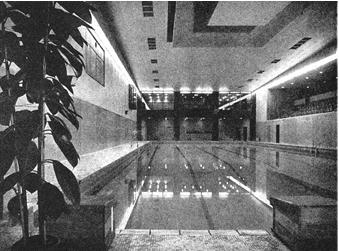

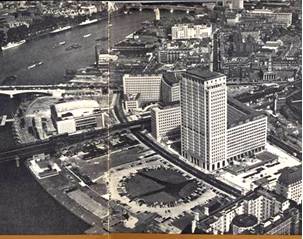

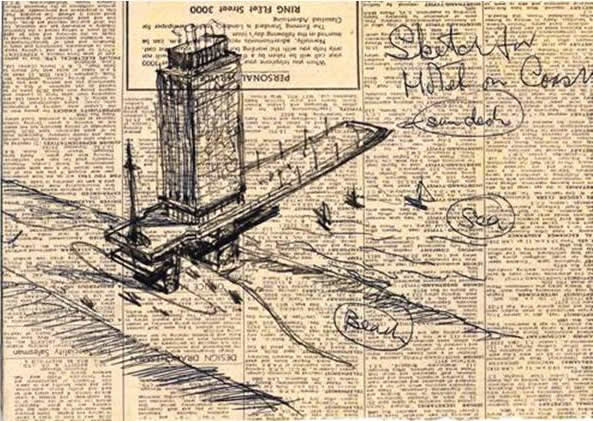

The site itself was bisected by Hungerford Bridge, carrying the rail link to Charing cross, which resulted in separate upstream and downstream buildings. The client’s requirements were for floor space of 43 acres to be contained on a seven-and-a-half acre site. The Centre was to accommodate 5,000 full-time staff and had facilities for exhibitions and recreation together with a fully equipped theatre. The sports facilities included a swimming pool (27) to international competition standards, which was situated 38 ft. below sea level.. Pages from RMS’s sketchbook show early visualisations of the Shell Centre project: ‘Tower by a Waterfront’ (28) was probably drawn at the time of the very first discussions of the project. A little later c.1954/5 (?) shows him beginning to work out the character of the lower blocks adjacent to the base of the Tower (29). Again in 1954, we see him assessing the aspect of the whole group of buildings as it would be seen form the north bank of the Thames in relation to County Hall, as it then was called. (30). Parts of the building came into use during 1962, before the official opening, and it has since enjoyed a very good reputation with those who work there. The Shell Tower was finished in 1963, only weeks ahead of the Vickers / Millbank Tower, with which it was in competition. It could therefore be called London’s first skyscraper (27-33). The Shell Centre will enjoy its jubilee in 2013. |

||

|

||

| 27. Shell Swimming Pool, part of the extensive sports complex, was designed to meet international competition standards. It is 38ft below sea level. Shell Photo Archive

|

||

|

|

|

||

| 28. Tower by a Waterfront. Drawing by RMS. Early 1950s. Recording his first thoughts on the Shell project | 29. Drawing by RMS, 1950s. Beginning to work out the aspect of the lower blocks adjacent to the base of the Tower. | 30. Drawing by RMS, 1954, assessing the Shell Centre as it would be seen from the north bank of the Thames in relation to County Hall (as it then was) |

31. Aerial view looking East. The Thames with Hungerford and Waterloo Bridges |

|

|

|

||

| 32. Looking West: upstream and downstream buildings in relation to the Festival Hall. Photos: Shell Photo Archive | 33. The Shell Centre, 1963 (Easton & Robertson, Cusdin, Preston and Smith). Partners in charge: Sir Howard Robertson and R. Maynard Smith. As seen from the North bank of the Thames in 2002, with the ‘London Eye’ and part of the old County Hall; the Festival Hall is just visible on the extreme left. Photo: A. Peters |

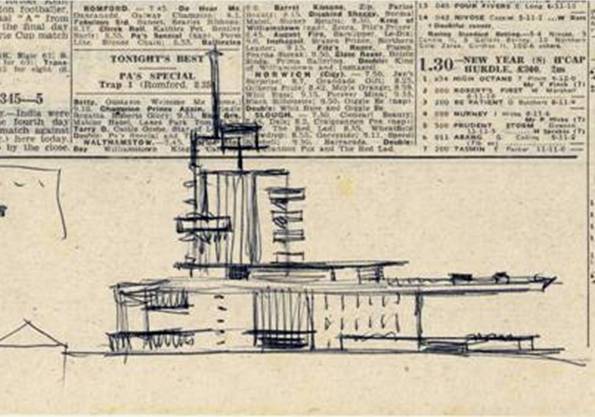

In fact the fabric of the Shell Tower already contained the seeds of a number of ‘post-modern’ towers that have since been built worldwide. All, like Shell, are individualistic and distinctive, whereas International Modernism, which was predominant in the early 1960s, required that the design of a tower should tend towards the simplicity of a matchbox with glass curtain walling. Some of those seeds, which are to be seen in the Shell Tower, were then unique and embryonic features: To quote here just three examples of post-modern buildings that illustrate those above-mentioned characteristics of Shell:- Two of the few surviving sketches for other schemes by Maynard Smith are shown below (34 & 35). They provide further evidence of his ‘post-Shell’ thinking, and give a clue as to how his future work as an architect might have developed. In the event he must have felt the prospect was too daunting, for he decided to retire, and he died suddenly the following year.

|

|

|

|

| 34. Sketch for ‘Hotel on Coast’. Drawing c. 1962 | 35. Sketch for ‘Hotel on Coast’ (another version). Drawing c.1962

|

| Return to top | All material copyright © RMS Trust 2012 | |